A previously unrecognised sedimentary archive in sand dunes could unlock a repository of fire records, a discovery that could expand fire histories across the globe.

The research, conducted by Dr Nicholas Patton during his PhD at The University of Queensland, has solved a persistent problem facing historians investigating changing fire patterns.

“Knowing how the frequency and intensity of wildfires has changed over time offers scientists a glimpse into Earth’s past landscapes, as well as an understanding of future climate change impacts,” Dr Patton said.

“To reconstruct fire records, researchers usually rely heavily on sediment records from lake beds, but this means that fire histories from dryland regions are often overlooked.”

“We’ve now shown that sand dunes can serve as repositories of fire history and aid in expanding scientific understanding of fire regimes around the world.”

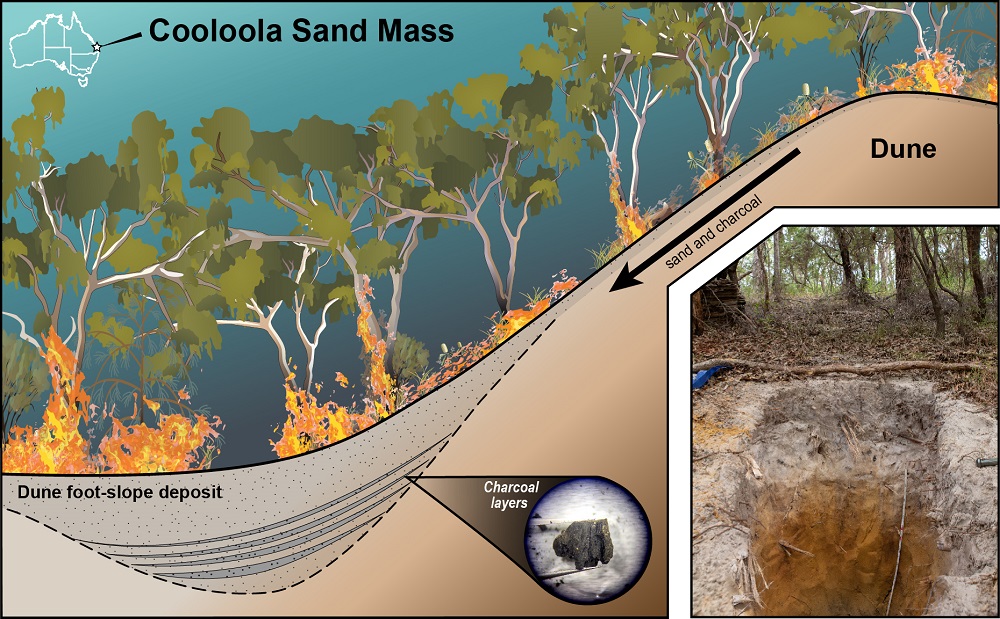

The study is the first to systematically examine sedimentary records preserved in foot-slope deposits of sand dunes – specifically, four sand dunes at the Cooloola Sand Mass in Queensland, looking at approximately 12,000 years of history.

The researchers aimed to prove that these sand dune deposits could be used to reconstruct reliable, multi-millennial fire histories.

“The Cooloola Sand Mass consists of large sand dunes that were created off the coast and moved inland from the power of the wind,” Dr Patton said.

“We were digging soil pits at the base of the dunes and were seeing a lot of charcoal – more charcoal than we expected.

“And we thought maybe we could utilise these deposits to reconstruct local fires within the area.”

They were correct, and were delighted to see that their dune-based fire history findings successfully matched other fire records from the region found in lake and swamp deposits.

“We found that on the younger dunes – at 500 years old and 2,000 years old – charcoal layers represented individual fires, because the steep slope of the dunes quickly buried each layer,” Dr Patton said.

“However, the older dunes – at 5,000 years old and 10,000 years old – had more gradual slopes that blended charcoal from different fires over time, providing a better understanding of periods of increased or decreased fire frequency.”

The dunes offered localised fire histories from within an approximate 100-meter radius, so fire records varied somewhat amongst the four dunes, which spanned approximately two kilometres.

“Similar records are likely held in sand dunes around the world, and regions like California and the Southwest U.S. could benefit from a better understanding of regional fire history,” Dr Patton said.

“Embedded within the fire records is not only information about natural wildfires, but also the way that humans influenced fire regimes.

“Fire histories are important for understanding how fire was used in the past for cultural purposes, whether that was to clear fields for agriculture or for hunting.

“These records have the potential to unlock the role climate and/or Indigenous peoples had on the landscape from regions where they are rare or absent.

“It would be exciting to see this work extended into the Kimberley and the dune areas along the northern Australian coast where humans have lived for tens of thousands of years.”

The research was conducted between UQ, The University of Canterbury and the Desert Research Institute.

It is published in Quaternary Research.

Media: Dr Nicholas Patton, nicholas.patton@pg.canterbury.ac.nz, +64 21 7 46 103; Faculty of Science Media, science.media@uq.edu.au, +61 438 162 687.