The University of Queensland’s Dr Graham Fulton has successfully unearthed over 80 previously unknown bird specimens, dusting off records from the historic 1875 Chevert expedition.

This marks the first time in 146 years that specimens collected from the expedition, then placed in the Sydney University’s Macleay Museum, have been discovered and discussed.

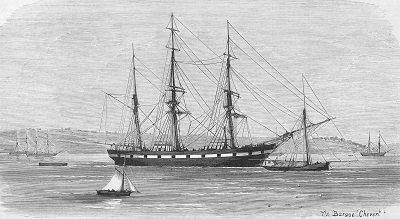

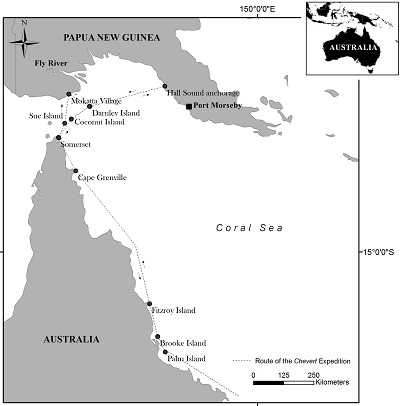

The expedition, which was the first Australian scientific expedition to a foreign shore, saw Sir William Macleay and a team of naturalists set sail to the then unspoiled islands of the Great Barrier Reef, the Torres Straits and New Guinea.

Their aim: to comb the islands in search of new birds, fish, reptiles, mammals, insects, Indigenous artefacts and more, to collect and showcase in Macleay Museum.

While the scientific community at the time considered the expedition a success, the mismanagement and uncareful handling of the specimens in the years following its completion has made accurately cataloguing its findings a difficult task.

Dr Fulton of UQ’s Centre for Biodiversity and Conservation Science and the School of Biological Sciences said the identity of birds collected during the expedition was incompletely published, and meant many important details were lost in translation between expedition members and curators at the Macleay Museum.

“Despite receiving detailed notes, the museum curator at the time’s species accounts rarely provided the critical data required, with the number of specimens collected and their sex being two important pieces of information missing,” he said.

“The accounts were disappointingly inconsistent and gave dubious locations that related more to the curator’s growing knowledge of the birds’ distributions than to their collection locality.

“Despite the efforts of curators and expedition members to clearly tabulate their findings, there were birds that slipped through the cracks and were not reported.”

Even more specimens were lost due to poor specimen storing and cataloguing practices.

“A lot of specimens were stored closely, underneath an iron roof and exposed to extreme weather fluctuations between summer and winter,” Dr Fulton said.

“Most of the specimens were irreparably damaged and some were even fostered out to private homes during wartime.”

Dr Fulton’s aim then became to identify and count the birds collected on the expedition in 1875, to get a more accurate and scientifically factual account of the findings and detail them in his most recent study.

“It’s a fascinating story that I was compelled to dig into to learn more about – my passion for this field of research led me in deeper,” Dr Fulton said.

“The study provides some general historic background on how and where the birds were collected.

“It doesn’t so much intend to report or discover the whereabouts of lost or traded specimens, so much as it aims to report in more depth the type specimens that were unknowingly discovered.

“It’s an important finding, as type specimens are the most valuable of all museum specimens.”

To do this, Dr Fulton gleaned three main sources of information: two official published accounts from expedition members and researchers of the birds, and the existing collection of birds held in the Macleay Museum.

Dr Fulton said some of the discoveries from the expedition are quite remarkable, so much that he envies the expedition crew and what they were able to find.

“Perhaps the most important finding was by Sir William Macleay, who noticed that the birds of New Guinea were transitional between the Australian bird-life and the Melanesian bird-life,” Dr Fulton said.

“I envy the expeditions discovering new forms of Kookaburra and many new species of birds – they were lucky enough to witness unspoiled habitats and countries.

“Expeditioners were journeying into an unspoiled paradise, free from many of the negative side-effects that come from Western society.

“It would have been totally foreign in every way and some animals discovered and sighted have since become extinct.”

While the discovery has answered some questions that lingered for 146 years since the expedition, Dr Fulton said there are more mysteries to uncover, a task he is game for.

“There are still a few known unknowns that need unearthing, and there may be unknown unknowns – who knows?” Dr Fulton joked.

“Somewhere in my future, I will likely attempt to dig deeper into the expeditioners’ pasts.”

The research has been published in the Proceedings of the Linnean Society of New South Wales.